"Tracked" Programs for Sparring and Forms

A Modern Taekwondo & Karate Skill Training Structure Informed by Current Scientific Theory for Growing Traditional Combat Sports and Strong Athlete Development Pipelines (5th dan thesis)

In taekwondo, it’s customary to write a thesis paper when testing for higher black belt grades. It’s meant as an opportunity to contribute something original and intellectual to the art, but in practice it’s a nominal task. However, I consider everything ultimately to be what you make of it. This is my taekwondo 5th dan thesis, and I made maximal use of the exercise.

Introduction: A Pedagogy in Disrepair

Based originally on the pedagogy of Japanese karate, the overall structure and progression of taekwondo (TKD) training has remained virtually unchanged since its emergence in the 1950s and 60s.

TKD's training format also seems to be consistent around the world, in large part due to the testing requirements and proposed curricular structures of the major international governing bodies—as well as the traditional spirit of the art itself.

Sport science has not been so idle on training research over the last several decades, however. Strong skill acquisition and motor learning literatures exist that can inform radically more effective and efficient training design for taekwondo.

Indeed, studies even exist on TKD specifically yet are ignored by most practitioners, including elite level coaches. The question then must be asked: why does this research never make it into the practice of actual TKD coaches?

Causes of Outdated Pedagogy & Program Design in Taekwondo

Governing bodies hold the most influence over training conventions in the international taekwondo culture.

The Kukkiwon (World Taekwondo Headquarters) and other major organizations claim to be scientific and/or to conduct original research, but curiously their findings to date have not spurred any meaningful changes in structure or methodology of practice.

In fact, they don't even seem to study these aspects of training and thus cannot suggest updates to the overall approach.

Outside Pressures

Intense pressure to change has also been exerted on taekwondo practitioners from outside, including Mixed Martial Arts, muay thai, and jiu jitsu athletes and coaches.

These voices do not promote an updated training methodology so much as they promote conformity with other combat sports, such as kickboxing. Most simply want to rid TKD of its beloved poomsae (forms).

This history of strife with critics has left taekwondoin with a strong belief that modernizing the training approach for TKD would mean robbing it of its traditional spirit and identity.

Inside Pressures

Sport taekwondo is torn between the demands of outdated views on pedagogy and skill acquisition from inside just as much as unfair demands from outside. Sport taekwondo in all its facets has a right to exist on its own without being judged by the standards of other combat sports and the idealistic expectations of non-sport or anti-sport elements inside TKD culture.

Nevertheless, the athlete development pipeline suffers because club-level training is dictated by outdated training formats and views. It seems absurd to bind sport taekwondo training with the opinions and ideas of individuals who do not care about sport TKD (or even dislike it).

Rationale for Pedagogical and Programmatic Update

In merit of the empirically-supported benefits for learners, it seems clear that the training methodology needs an update, especially for the sake of sport growth.

This paper helps accomplish that task by synthesizing the essence of taekwondo with current theory in the skill acquisition sciences of motor learning and motor control.

It offers an innovative structure of practice and program design that keeps poomsae and other formal modalities in training while still allowing for student freedom over their own learning and more focused, evidence-based training to support their paths.

In other words, this work strives to update the methodology without simply transmorphing taekwondo into kickboxing or MMA.

Instead, it provides a brief scientific rationale and a proposed structure for separating formal and sparring-oriented activities into their own program "tracks.” This general structure can be applied to any so-called traditional martial art that has a combination of forms practice and sparring.

Overall, though, the main purpose of this work is to help governing bodies and local clubs design training programs that create stronger, more successful athlete development pipelines.

Current Motor Learning Theory in Brief

With pressure always rising to perform at the Olympics, national governing body USA Taekwondo (USATKD) has turned its attention to improving its athlete development pipeline. Without changing the standard training practices of local TKD clubs, however, their efforts are most likely to yield a middling return at best.

But armed with the most current science in skill acquisition, USATKD and other organizations could work with local clubs and coaches to build much more productive and reliable athlete development pipelines.

To understand skill acquisition, practitioners and sport officials must first understand motor skills.

Coker (2009) defines motor skill as an act or task action that satisfies four criteria:

1. It is goal-oriented, meaning it is performed in order to achieve some objective.

2. Body and/or limb movements are required to accomplish the goal.

3. Those movements are voluntary. Given this stipulation, reflexive actions, such as the stepping reflex in infants, are not considered to be skills, because they occur involuntarily.

4. Motor skills are developed as a result of practice. In other words, a skill must be learned or relearned.

Not all skills are the same. That is, not all skills impose the same kinds of constraints or burdens on a human mover. Rather, motor skills fall on a large spectrum between closed skills and open skills.

Closed skills are performed in predictable environments, with little or no change during an activity. Open skills, on the other hand, are performed in “unpredictable, ever-changing” environments.

Naturally, the difference in skill demands creates a difference in demands on the motor control system of a mover or athlete. This difference in mechanism of control creates a necessary difference in the way movers train for those skills.

Coker (2009) further explains:

The closed/open distinction is an important one for practitioners, as the instructional goals for each differ significantly. For closed skills, consistency is the objective, and technique refinement should be emphasized.

For open skills, where the learner must constantly conform his or her movements to an unstable, unpredictable environment, successful performance becomes less dependent on mastering technique and more dependent on the learner’s capability to select the appropriate response in a given situation. (emphasis added)

Some examples of closed skills include buttoning up a shirt, shooting a hoop from a stationary position, and shooting a firearm at static targets. It also generally includes poomsae and kata.

Examples of open skills include walking through a crowd of moving people, passing guard in jiu jitsu, and punching a moving opponent in boxing or kicking a moving opponent in taekwondo.

Skill Analysis: Taekwondo Poomsae and Kyorugi Classified by Gentile’s Taxonomy

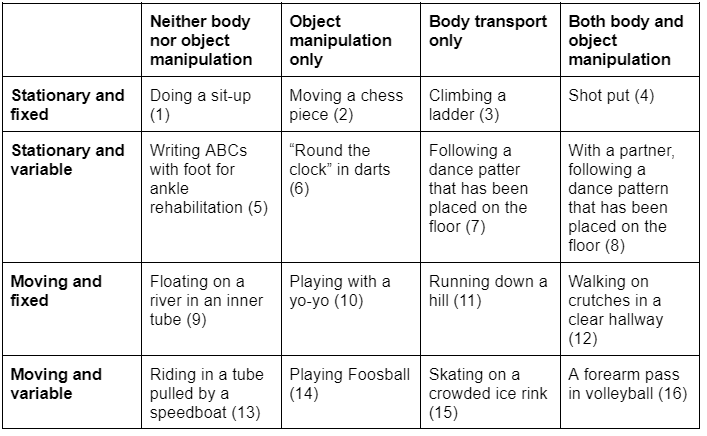

A researcher by the name of A. M. Gentile proposed what he called a “multidimensional classification system” for motor skills, also known as Gentile’s taxonomy (Coker 2009).

This system has become a professional staple among physical therapists and other movement practitioners because it allows practitioners to know where a given skill falls along the closed/open continuum.

The two main dimensions of this system are (1) the context of performance and (2) the action requirements of a given skill. Sport scientists and other researchers call these dimensions regulatory conditions and action requirements, respectively.

Moreover, analyzing a skill according to these two factors will reveal how that skill is best acquired (Coker 2009). The taxonomy is reproduced below.

This paper will analyze poomsae first and kyorugi second. To determine where forms or poomsae fit, one must first describe what poomsae is. Poomsae are solo exercises where an individual performs a prearranged sequence of attacks and defenses, following a set stepping pattern on the floor.

Poomsae do not include object manipulation in the form of acting upon an opponent, and there is no variable opponent or object operating in the environment against the poomsae performer. Poomsae performers must move (body transport), but they do not have to manipulate an object. This rules out action requirement subdimensions 1, 2, and 4.

There are also typically no variable conditions in the environment whenever a performer performs a poomsae (esp. no opponent), but the place where you start and end in a poomsae might change slightly between practice trials. Coker’s example of a category 7 activity was a dance performed to a set floor pattern (2009).

So because this appears to most closely describe poomsae, this paper regards poomsae as category 7.

In stark contrast, the skills necessary to be successful at kyorugi share key underlying dynamics that place it in category 16 of the taxonomy.

All three of these activities necessitate skills that require

Body transport (footwork)

Object manipulation (acting upon, controlling an opponent)

Moving regulatory conditions (an active opponent)

Variable inter-trial conditions (opponents who act and respond differently every match or engagement, even within engagements)

Because all 4 of these factors accurately describe sparring, this paper contends it is in category 16. Therefore, the proper training methods that sparring entails are very different from poomsae (Coker 2009).

The following section presents an updated training methodology for kyorugi (and potentially for poomsae) training grounded in current skill acquisition research.

The Constraints-led Approach to Motor Learning & Coaching

The Constraints-led Approach (CLA) is a current model of motor learning and coaching that provides guidance on how to use “ecological” learning principles in sport training environments. The term “constraint” refers to any nominal or concrete element in a system that limits the degrees of freedom available to it behaviorally (Button, et al. 2021).

The basic proposition of CLA is that skilled behavior emerges from experience shaped by three categories of constraint: individual, task, and environment (Renshaw, et al 2018).

These constraints constantly interact to produce movement. This has several implications regarding motor control that clash with the traditionally dominant view of control among taekwondo instructors.

In summary, CLA is underpinned by a theory of perception that sees learning as an ability to perceive information in the environment that specifies how to act (Button, et al. 2021; Renshaw, et al. 2019).

This requires that effective training retains enough informational overlap in the environment so that the perceptual “attunement” and resulting skill improvement transfer to the performance environment.

Motor control therefore requires that the right information for action be present in the practice environment if it is to have a high probability of showing up skill-wise on competition day.

The key pedagogical and program design considerations of CLA for the purpose of this paper are contained in its four learning environment design principles.

Session intent. The specific purpose of the practice; what it intends to achieve through its selection and progression of exercises.

Constrain to afford. Manipulating task and environment constraints in a way that helps players notice and use the right information for action. In martial arts terms, it’s using modified life practice environments to help students learn to read openings.

Representative learning design. Designing practice exercises that have the right kind of overlap with the dynamics of the performance environment being trained for, i.e. the “real thing.”

Repetition without repetition. Designing practice tasks that allow players to solve the same problems in different ways (instead of providing them with pre-made solutions).

All four environment design principles of CLA require that training for a given sport represent the true dynamics of that sport to a sufficient degree. “Representativeness,” so to speak, is a tradeoff, since it is impossible and counterproductive to always train with full sport rules at full sport intensity (Renshaw, et al. 2019; Button, et al. 2021).

However, it is necessary that some basic dynamics always remain to insure that the information perceived in these practice exercises has fidelity to the actual sport environment.

CLA repositions the coach from an instructor of prescribed solutions to a designer of enriched learning environments (Renshaw, et al. 2019). In other words, the coach creates domain-specific problems for learners to solve, and in the process of solving, learners improve.

These problems, again, are representative of the sport. They retain a sufficient dynamic overlap with the target environment in question so that the information detected by learners is likely to be present to inform their action when performing “the real thing.”

Implications on Taekwondo Pedagogy & Program Design

Instructors traditionally attempt to transfer knowledge to students by providing them with solutions to problems, often before the problem has even been experienced in earnest (DeMarco & LaFredo, 2015). Both Korean martial arts and the traditional coach-athlete relationship maintain a strict hierarchy of dissemination from teacher to pupil.

Personal exploration is sometimes encouraged, but the dominant attitude among taekwondo practitioners is that the master generally knows best. The athlete’s input is typically assigned minimal importance.

Viewing TKD training through the lens of current motor learning research changes things.

First, the informed coach understands the different facets of taekwondo in terms of the actual dynamic and motor control demands–the type of skill. Poomsae is more of a closed skill while kyorugi is an open skill, and the TKD coach understands these are very different kinds of skills that demand unique styles of training.

Second, the informed coach is not a solution-giver but rather a designer of learning environments wherein students can solve problems in a realistic, representative way. Athletes adapt to their learning environments as they solve these problems through search, exploration, and play–and that is how they improve.

Coaches help students forge their own paths, facilitating practices targeted to the sport in question rather than forcing a singular practice style for tradition’s sake.

In this way, students are able to more rapidly build skill and experience less friction while trying to study the aspect of taekwondo in which they’re most interested.

The constraints-led approach extends the basic stipulations of Coker’s open/closed skill practice and Gentile’s taxonomy. Not only are proper poomsae and kyorugi practices very different, but kyorugi practice in particular should be very different from how the conventional taekwondo sparring class is conducted now.

CLA’s principles of representative learning design and repetition without repetition strongly suggest that much of the drills and patterns thought of as “practical” are in truth not very useful for producing competition-ready kyorugi skill.

Consequently, this paper recommends that nearly all of kyorugi practice time be spent in some degree of live training (“live” or “aliveness” is defined in greater detail in the next section).

Taekwondo training right now is confused, made up of dozens of training methods vying for play time during a 45-60 minute class on top of curriculum requirements. There is kibon (basics practice), combinations, flow drills, forms, one steps, self-defense sets, sparring, paddle drills, shield drills, hogu drills, calisthenics, stretches, and more.

It is impossible to get adequate re-exposure to the right exercises to improve skill in any one aspect of TKD, much less all of them.

With the tracked program this logistical problem is resolved. Each track ensures it fills class time only with the most useful exercises for developing skill. Students get adequate repetition of the right training methods because they aren’t spreading practice time between several separate skills within taekwondo.

Consequently, clubs are empowered to produce highly skilled athletes in both poomsae and kyorugi and contribute positively to the sport development pipeline.

Reorganizing Taekwondo Training into Sport-Specific "Tracks"

Sport taekwondo as regulated by World Taekwondo (WT) consists of two primary events: kyorugi (Olympic sparring) and poomsae (solo or synchronized performance of forms). The International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF) has a similar division of events.

As an aside, according to the World Karate Federation (WKF) and similar organizations, karate’s two main sport events are the same: sport kumite (sparring) and kata (forms).

Traditionally, forms and sparring have often been thought of as interconnected for skill development. One step sparring, board breaking, and myriad other formal and repetitious drills also fill out the training program in most clubs and vie for class time on the assumption that they somehow contribute to overall combative skill.

However, no empirical evidence exists to support this belief, and current motor learning research appears to actively disprove it. For this reason, the skill-developing connection between formal and dynamic aspects of taekwondo performance needs to be critically reexamined. The previous sections attempted this in brief, but more extensive work is necessary to fully detangle culturally persistent beliefs in taekwondo about the relationship of formal and functional training methods.

Based on the summarized skill acquisition literature, it should be clear that poomsae and kyorugi are not just different competition events but entirely different sports. They both belong under the banner of taekwondo, of course, but they are in no way related to one another in terms of athletics, dynamics, or motor control demands.

Thus, focused training programs for each sport require that practice sessions consist of methods that are not mixed between formal and sparring-related exercises. Focused poomsae classes must exclusively use formal exercises, and kyorugi classes must exclusively use functional, sparring-based exercises.

Therefore, this paper proposes that governing bodies and educational organizations encourage taekwondo clubs to divide their programs into sport-specific, unmixed kyorugi and poomsae tracks, respectively.

The following subsections provide an overview of the shape of each track as envisioned by this paper.

Kyorugi/Kumite (Sparring)

The full breadth of current best practice design considerations for sparring programs is beyond the scope of this paper. An entire book could be written on the scientific updates that need to be made to kyorugi training alone.

Rather, the purpose of this subsection is to overview the proposed shape and identity of a taekwondo sparring program track as it contrasts with the poomsae track.

Coined by Bruce Lee and popularized by MMA coach Matt Thornton, the term “aliveness” is commonly used by martial artists across categories to describe exercises that involve genuine combative decision-making and physical interaction. This is chiefly expressed in free sparring, but free sparring is not the extent of alive or “live” training.

For this reason, several definitions of aliveness exist. This paper adopts the following definition:

Aliveness is tactical behavior between two performers that is both unscripted and uncooperative at the same time.

This definition is necessary because some coaches present exercises as “live” that do not match the dynamics of sparring which make sparring alive. That is, they present exercises that are unscripted but otherwise compliant (cooperative) or uncooperative but nevertheless scripted.

Free sparring – and more importantly, sport kyorugi – is never scripted and never cooperative in nature. Any exercise which is not both unscripted and uncooperative at the same time breaks the aliveness and diminishes its utility for kyorugi training (Button, et al. 2021).

Sparring classes isolated from the main curriculum are fairly common in the US. Even with such limited training time in sparring, however, these classes still tend to be filled up with “dead” drilling, sterile repetitions, and extraneous conditioning exercises.

Engaging in the act of sparring, the actual sport, takes up a surprisingly small part of actual practice. It is no wonder that grassroots level competition circuits are so underdeveloped, at least in the USA.

Therefore, sparring classes should focus on achieving 90% or greater practice time in live exercises and/or sparring. This is the most representative type of training and so most likely to develop skills that transfer to sport performance (Button, et al. 2021).

Poomsae/Kata (Forms)

The tracked program concept holds poomsae as an intrinsically valuable aesthetic, cultural, and meditative practice. It is also an interesting exercise in balance, proprioception, and muscle control.

As such, poomsae's value does not hinge on the perceived “practicality” of its movements or applications.

Current taekwondo pedagogy is already focused on formal training, chiefly poomsae. CLA can still help improve it, but overall taekwondo practitioners already know how to teach poomsae, one steps, and other formal exercises fairly well.

Classes should center not just around poomsae practice directly but also flexibility and strength and conditioning exercises that facilitate powerful movement in poomsae competition performances. Further, training should be organized toward competition poomsae.

Even students who do not compete benefit from this type of training. Moreover, it keeps the practice of the same poomsae fresh and interesting from year to year.

Poomsae is a formal practice as well as a sport, so other practices considered central to formal TKD (board breaking, one steps, etc.) should be included in the poomsae track and kept out of the sparring track.

Tracked Program Benefits

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a well-evidenced and widely accepted view of motivation, especially how to understand and foster the coveted intrinsic form of motivation.

In short, intrinsic motivation is the most powerful and sustainable form of motivation, most associated with overall well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

SDT proposes that intrinsic motivation is best cultivated when the human learner’s basic psychological need for autonomy (self-direction), competence (skill learning), and connectedness (sense of community) are met.

The current structure of the taekwondo curriculum does not support autonomy and competence and thus undermines intrinsic motivation to participate in both the art and sport. Some learners just like poomsae, some only like kyorugi, and some like both (DeMarco & LaFredo, 2015).

It is often the case that athletes can promote with only poomsae and formal exercises (such as one steps), but it is never the case that kyorugi athletes do not have to perform poomsae and one steps in order to advance rank.

The taekwondo curriculum as it exists today has a strange bias to it relative to its own international sport structure and lacks options for individuals who want to pursue kyorugi without being bogged down by formal material, for example.

It is also the case that some poomsae athletes are forced to spar when they rank upward. More often than not, this results in very subpar performance and yet nearly as often they are passed to the name rank anyway.

If the performances are nominal, why require them at all? How can these truly be considered tests?

What do they actually demonstrate, and what does that say about the TKD and karate training cultures as a whole?

This will never be fixed under the old system, and it does not promote excellence in taekwondo. This paper maintains that the current curricular structure hurts the art, the sport, and the people who love it, by forcing them to engage in functionally separate sports they do not like. It removes their agency (autonomy) from studying taekwondo in the way most interesting and engaging to them.

Sport taekwondo should be accessible to everyone. Poomsae athletes should not have to spar (in fact, this is often already the case) in order to progress; and naturally, kyorugi athletes should not be forced to do poomsae to progress, either.

Some people love taekwondo for the intrigue of sparring competition, some love it because of the self-work of poomsae, and some love it because of both. It is all taekwondo, and it should not be vilified as incomplete or inauthentic simply because one aspect of it is not actively practiced.

Athletes should be able to choose at any point in their learning journey if they want to focus on formal material, sparring, or both aspects of taekwondo. To do so leaves their autonomy intact, enhances their connectedness, and ensures that any competence-supportive feedback is always appropriate to their interest.

Furthermore, it removes unnecessary friction for athletes with competitive aspirations and dissolves embarrassing displays of subpar skill during testing.

Finally, the tracked program’s sport-specific structure facilitates the development of far more skilled athletes in both sports than the previous model.

Tracked Programs & Belt Ranking

As established, the kyorugi and poomsae events are separate sports with unique athletic and motor control demands. The tracked program structure accommodates focused training in these different sports by separating them into their own distinct (and unmixed) class formats and curricula.

As a result, athletes will have differing skill levels between the two program tracks. Therefore, separate ranking systems will be necessary for each sport track.

Candidates for Ranking Differentiators

Gup/dan (or kyu/dan) grades and belt color are an entrenched and longstanding part of both kyorugi and poomsae competition systems. Tracked programs thus should keep the belt system, even if only for greater expedience.

With the different tracks in mind, then, it is recommended that color differentiators be added on belts to indicate to which program track it corresponds. Reserved stripe colors and multi-color belt styles are both candidates.

Uniform style (e.g., v-neck vs robe jackets) are also good candidates to further demarcate between tracks–and have corresponding sport usages already established within WT.

Problems to Solve Under the Current System

This does not resolve all ranking problems, however. The Kukkiwon and most other organizations require mixed testing criteria for dan (black belt) ranking. Some organizations and individual clubs forgo live sparring entirely; most require sparring as well as a heavy dose of formal curriculum.

Regardless, these mismatched testing criteria create a problem for specialized athletes who desire organizational rank certification but consequently cannot meet some or most of those requirements.

This is a hard institutional constraint for students who wish to seek organizational recognition. Inter-institutional change will be necessary to eventually accommodate specialized athletes, but this will likely be a decades-long battle before it is realized.

Coaches therefore will have to develop their own adaptations to and compromises around this problem in the meantime.

Conclusion

Since its founding and popularization in the mid-late 20th century, taekwondo pedagogy has remained relatively unchanged regardless of parallel advancements in the science of skill acquisition.

The exploration of current motor learning theory in the context of taekwondo training offers valuable insights into how student learning experiences and athlete development pipelines can be optimized.

Motor skills are classified into closed and open skills. This construct provides a foundation for tailoring training methodologies to specific skill demands.

The distinction between poomsae and kyorugi as separate sports with distinct skill sets underscores the importance of specialized training tracks.

Poomsae, being more of a closed skill, benefits from focused formal exercises and flexibility training; while kyorugi, being an open skill, necessitates live sparring for dynamic decision-making practice.

Implementing sport-specific tracks ensures that training time is dedicated to exercises that directly contribute to skill development in each discipline. The Constraints-led Approach (CLA), specifically, provides taekwondo practitioners with the tools to design more effective training programs and engage in more effective coaching behaviors.

The tracked program structure not only enhances skill acquisition but also fosters intrinsic motivation among practitioners. By allowing individuals to pursue their preferred aspect of taekwondo—whether poomsae, kyorugi, or both—while maintaining autonomy and competence, the tracked program promotes a more engaging and fulfilling training experience.

Moreover, it eliminates the friction caused by forcing athletes to engage in activities they do not enjoy or excel in.

Practical considerations, such as belt ranking systems, need to be adapted to accommodate the specialized nature of each track. Separate ranking criteria for kyorugi and poomsae, along with visual identifiers on belts, can signify an athlete's proficiency in their chosen discipline.

However, addressing institutional constraints surrounding dan ranking criteria may require broader inter-institutional changes over time.

Transitioning to sport-specific tracks in taekwondo training represents a significant advancement in optimizing athlete development and promoting a more inclusive and fulfilling training environment.

By embracing current motor learning theory and tailoring training methodologies accordingly, taekwondo practitioners and organizations can cultivate a new generation of highly skilled and motivated athletes, ultimately elevating the sport onto a new level of excellence.

References

Button, C., Seifert, L., Chow, J.Y., Araujo, D., Davids, K. (2021). Dynamics of skill acquisition: An ecological dynamics approach (2nd ed.). Human Kinetics.

Coker, Sheryl A. (2009). Motor learning & control for practitioners. Scottsdale: Holcomb Hathaway, Publishers.

DeMarco, M.A., LaFredo, T.G. (Eds.). (2015). Taekwondo studies: Advanced theory and practice. Santa Fe: Vie Media Publishing Company.

Renshaw, I., Davids, K., Newcombe, D., Roberts, W. (2019). The constraints-led approach: Principles for sports coaching and practice design. London: Routledge.

Ryan, D. & Deci, E.L. (2018). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New Guilford Press.