How do we actually control our movements? [How We Learn to Move, Chapter 3 Companion]

Your brain doesn't (directly) control as much as you might assume.

Every day, you reach out to grab a glass full of a beverage and achieve the perfect pressure such that you do not break the glass; yet the friction is enough to keep it from falling out from between your fingers.

You then bring it to your lips with barely a glance, maybe without even looking, tilt it just right, and empty just enough to quench your thirst before placing it softly back onto the countertop.

What’s happening here is remarkably complex—so complex, in fact, that advanced robotics technology still struggles to replicate it. From the standpoint of computation, the amount of calculation throughout the course of this simple movement is massive.

And where a robot has trouble picking up one glass of one shape, you likely could reach and drink from an almost infinite array of glass shapes, without practice, with no difficulty at all.

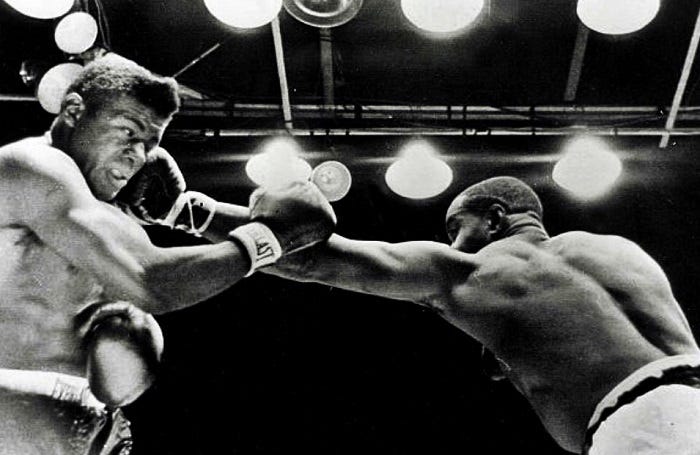

Now think of a jab.

Once you become skilled at it, you can pop them out of nowhere. You gauge distance, you stop onslaughts, you set up combinations, create information.

You don’t do conscious calculations. You don’t have to scheme and preplan when, where, and at what level to throw the jab.

It feels like it emerges when it needs to. It feels like an instinct—like it’s automatic.

So how do we actually do this?